With Europe’s attention squarely set on Ukraine, few have noted the rising tensions in the Western Mediterranean, between Morocco and Algeria. Yet, the recent clashes around the Western Sahara, the so-called “last African colony”, have caused sparks that risk re-kindling the braziers of war in the region, which have been held in check since 1991, but never completely extinguished.

The Western Sahara conflict is what experts call a frozen conflict. Why talk about it, then? First of all, because of the concrete risk of having another war in the European neighbourhood and the consequences that this would have on millions of people. Then, also because of the nefarious effects it would have on energy and food markets, already rattled by the war in Ukraine. It is, after all, those same experts who would point to the fact that even frozen conflicts can flare up suddenly and violently, as the case of Nagorno-Karabakh demonstrates.

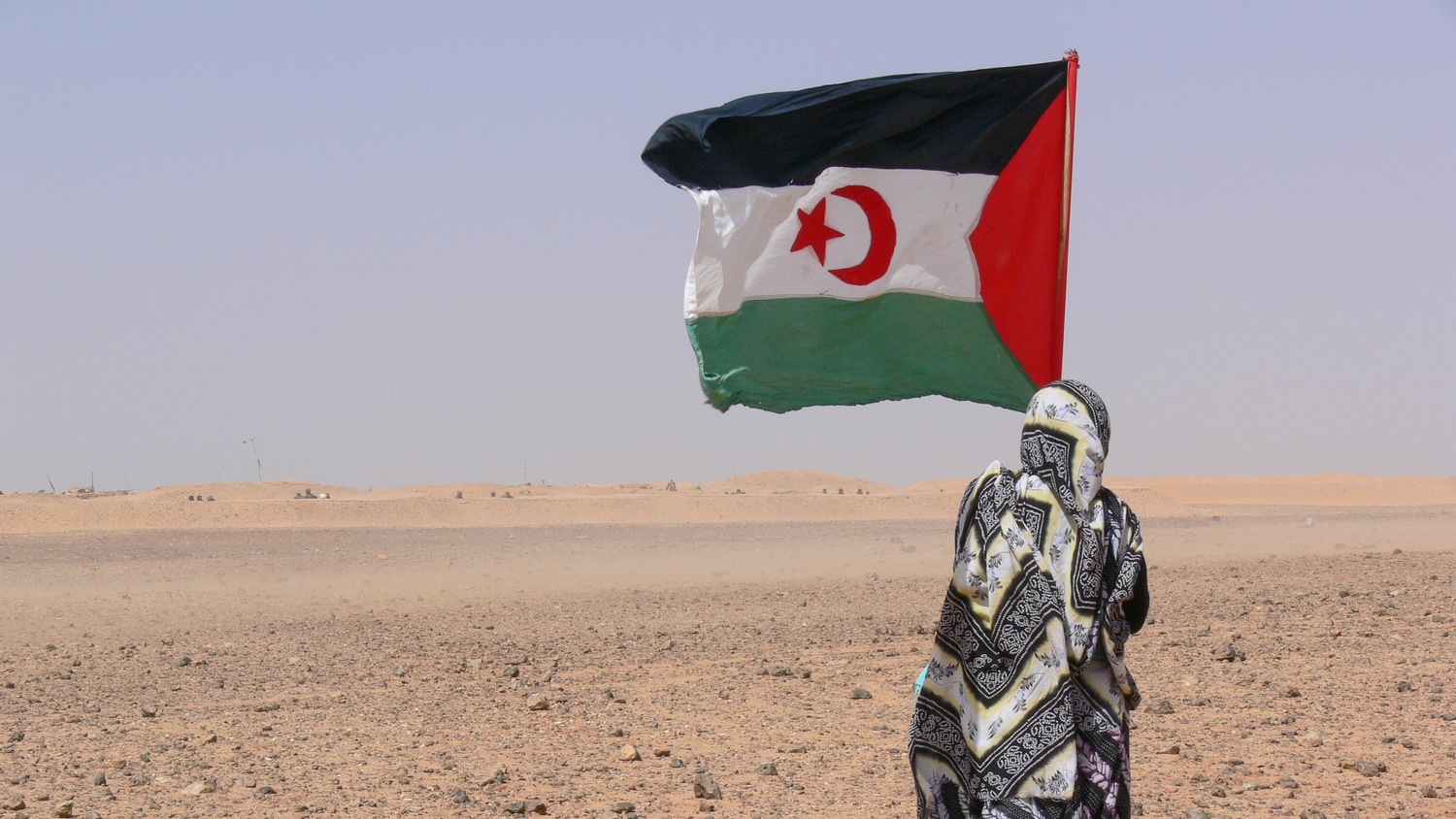

The Western Sahara is a large territory (roughly the size of the United Kingdom) located along the Atlantic coast between Morocco in the North and Mauritania in the South, just below (and facing) the Canary Islands. The conflict is about who controls the territory: it involves, on the one side, the Kingdom of Morocco and, on the other, the national movement known as the Polisario Front and its most important supporter, Algeria. The conflict started in the early 1970’s, when the Western Sahara was still a Spanish colony. Since then, the Polisario Front has been claiming the territory’s independence on behalf of the Saharawi people who live there and to whom the right of self-determination has been legally recognised. When Spain withdrew in 1975, the territory was immediately occupied by Morocco and Mauritania. The latter left in 1979, effectively defeated by the Polisario Front, while armed conflict with the former lasted until 1991. Then, the two sides signed a ceasefire agreement that should have brought about a referendum on independence, under the aegis of the United Nations.

The referendum, however, never took place, and Morocco has always resisted the idea of abandoning the Western Sahara: it controls 80% of the territory, including its large phosphate deposits and plentiful fish stocks, resources that contribute significantly to its economy. Since 2006, the Kingdom has furthermore pushed an alternative to the referendum—an autonomy plan that would leave the Western Sahara under its sovereignty. The Polisario Front has always rejected this plan, playing, however, on an uneven field. Morocco can count on strong visibility, powerful allies (the United States and France), and a strategic importance linked to the war on terror. The Polisario Front has no resources other than those that come from Algeria, a country that itself is going through a deep social and political crisis in recent years, and from humanitarian organisations. The Front is also far removed from the attention of international media, in large part because of the efforts of the Moroccan regime, which has treated any conversation on the final status of the Western Sahara, whether between states or citizens, as tantamount to treason.

Morocco’s delegitimization strategy seems, however, to have reached the limits of its effectiveness. Morocco has indeed reaped important results, among which the recognition of its sovereignty over the Western Sahara by the United States (under Trump), and also support for its autonomy plan by European countries like Spain and the Netherlands. Yet, the costs have also been high. At the end of 2019, the Polisario Front finally abandoned the 1991 ceasefire and reprised its armed struggle. In 2021, then, Morocco and Algeria broke diplomatic ties, while the United States (under Biden) effectively froze its recognition of sovereignty. Meanwhile, Algeria’s position has been strengthened by the energy crisis, which has brought the country closer to Europe (and France and Italy in particular) and allowed it to retaliate, for example through the suspension of its friendship treaty with Spain.

All these actions mark a clear escalation towards war. And while this may still appear far off, it should nevertheless be treated as inevitable insofar as there are no alternatives. “The Saharawi people have had enough”, said Minetu Larabas Sueidat, a Saharawi activist and the formed Secretary-General of the National Union of Sahrawi Women, “and it no longer believes what the UN says. People want independence and at this point they believe that the only way to obtain it is through armed struggle”. Morocco also seems bent on pursuing its uncompromising policy: “I expect”, the Moroccan king, Mohammed VI, has recently said, “that those allies of Morocco, whose positions relating to the Sahara issue are ambiguous, will clarify where they stand in such a way that no space for doubt remains”.

Those working on a political and non-violent solution to the conflict remain few, chief among them the UN and their special envoy, Steffan de Mistura. De Mistura is an Italian-Swedish diplomat with a high-level profile (he previously served as the UN Special Envoy for Syria), who has clearly stated his intention to look for a new formula to resolve the conflict. The use of the term “formula” is interesting in its own right: it refers to a general idea or a shared definition of a problem and its solution, which, once found, can serve as a basis for bargaining and making the compromises necessary to advance negotiations. It is, however, hard to imagine how de Mistura can find a formula able to balance the principle of self-determination that is at the centre of the Polisario Front’s requests and that of territorial integrity behind Morocco’s position.

A different, more successful formula could instead be found by expanding the focus of the negotiations and engaging new actors. The energy crisis could, in this case, represent an opportunity to launch a wider dialogue, involve the World Bank and create economic incentives towards a mutually acceptable solution. This is what happened, for example, with the Indus Waters Treaty signed by Pakistan and India in 1960 and still in place.

Whatever formula may be found, what is first and foremost necessary is to cool the conflict, or, in other words, to lead it back to a point where dialogue can take place. To do this, the first step is, without a doubt, to ensure that conversations on the final status of the Western Sahara can once again be treated not just as necessary, but, most importantly, as entirely legitimate. This will make it possible to start launching open and transparent dialogue anew, and at all levels.

Bernardo Monzani is the President of Agency for Peacebuilding.

The article was first published by “Il Mulino”, an Italian magazine covering culture and politics, on September 22, 2022. The original article, in Italian, can be accessed here.