This article is published as part of AP’s work in support of the Youth, Peace and Security agenda, as defined by UN Security Council Resolution 2250 (2015). To learn more about our work and read the other articles published, please click here.

Poverty afflicts more than half of the population of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), a newly formed autonomous region in the southern part of the Philippines. Riddled by violent conflict and a quest for self-determination that has lasted for more than four decades, this region suffers from low education outcomes, high unemployment and identity conflict issues. These factors have impacted young people in particular, who do not have voice or agency to participate meaningfully in community life, or in making decisions. In this region, young people are vulnerable both as victims of violence, and as perpetrators.

How does one then rethink development approaches for youth in regions affected by conflict? A potential answer is social enterprises, which the British Council has been using in the Bangsamoro context with the aim of simultaneously tackling conflict, social divides and economic barriers affecting young people specifically. This is the experience of the Strengthening Civil Society Participation in Social Enterprise Education and Development (CSO-SEED) project, and it could represent a model for other organizations and other regions affected by the same challenges.

What are social enterprises? Social enterprises are businesses driven by a public or community cause (be it social, environmental, cultural or economic), which derive most of their income from trade (not donations or grants), and use the majority of profits to work towards their social mission.

A political economy analysis conducted prior to the start of the CSO-SEED project revealed that the youth labour force participation in the BARMM was only 35.1%, and almost a quarter of people aged between 15 to 24 were neither in school nor in the workforce. Lacking the skills to productively participate in the labour market, out-of-school youth were, and continue to be, at high risk of poverty and disaffection, which potentially can lead them to violence and undermine social cohesion. Poverty is also closely linked to displacement, which is one of the defining characteristics of conflict in this region. Even minor spikes in violence can lead to large-scale population displacement. Between 2000 and 2012, for example, over 40% of families in Central Mindanao were displaced at least once, and the proportion of displaced families was as high as 82% in Maguindanao. Displaced populations invariably fare much worse than those that have never been displaced, according to such indicators as food consumption, access to basic services, and trust in both government and other ethnic/religious groups.

The CSO-SEED project, supported by the European Union, was designed to foster civil society participation in policy reforms that support decent work, job creation, and the development of social enterprises in the BARMM. The project aimed at promoting inclusive economic development; foster solutions to chronic problems such as lack of access to decent jobs and poor education outcomes; and help deeply fractured communities to heal. The logic behind the project was that, by creating jobs and supporting local youth to reclaim their identity and find a renewed sense of purpose, this would remove incentives for young people to join criminal gangs or rebel militias.

The focus on social enterprise prioritises not just economic outcomes but also social outcomes as an essential foundation to support stability. Social enterprises nurture creativity innovation and resourcefulness, and they help build resilient and adaptable communities. In 2017, we produced a national social enterprise landscape study and found that in the past decade in the Philippines one out of four social enterprises was started by a millennial. This showed that there was a need to further support young people to establish their own ventures. Together with our partners, we therefore ran youth-focused activities on active citizenship, advocacy and enterprise development to build a network of future leaders who can use entrepreneurship to solve social problems.

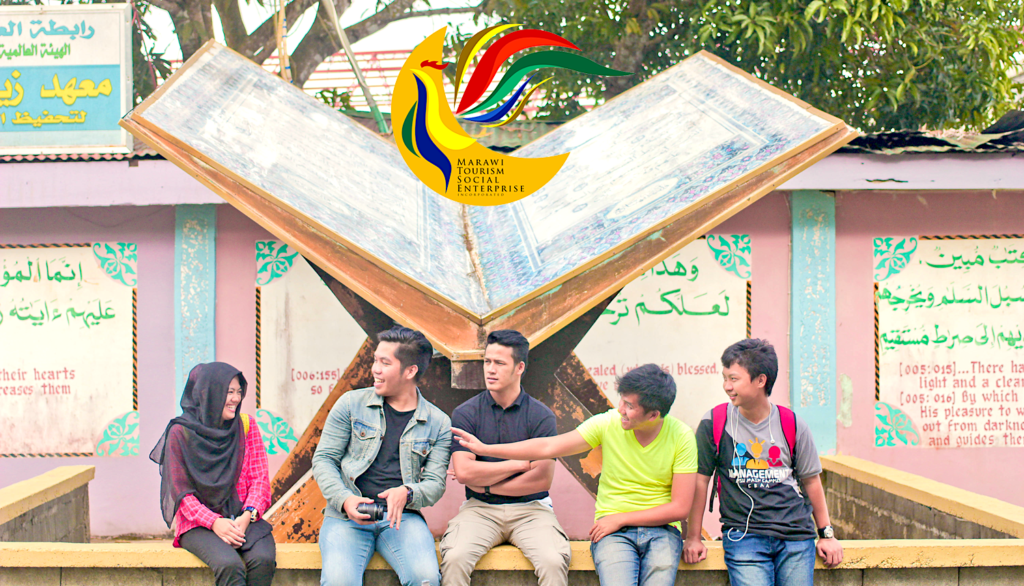

One of the enterprises established under CSO-SEED is the Marawi Tourism Social Enterprise (MTSE). This is a youth-led social enterprise that aims to revive culture and tourism in Marawi City in the wake a five-month armed conflict between ISIS-inspired militants and government forces. The CEO of MTSE, 24-year-old Annas Deriposun, says that the Marawi crisis has deeply affected lives and livelihoods in the city. In response, MTSE started to provide opportunities to internally displaced people and out-of-school youth, which coincided with a period when extremist groups were being more aggressive in their recruitment of young, impressionable youth. “With our exposure in CSO-SEED”, Annas said, “we have learned to work with various stakeholders, brokering relationships between our community, the government, the business sector, non-profits and CSOs. As a result, we build trust within our communities”.

Started in December 2017, MTSE now has five staff members and six artisans. The artisans receive at least 1.000 pesos (around 20 USD) for each completed product, including items such as a puzzle modelled from the heritage house of the Maranao called the torogan. According to MTSE’s co-founder, 23-year-old Abdulrashid Dimnang, MTSE’s interaction with young people has pointed to the lack of income as the main reason why they feel vulnerable: “at the end of the day they need food on the table, that is very basic”. Abdulrashid then added that during a feedbacking session a participant said that if only there had been opportunities such as this before, maybe the Marawi siege would have never happened.

The experience of the CSO-SEED project shows that youth participation is an instrumental principle that can make governance and the development process more effective and responsive to the needs and interests of young people. Key to this is how the social enterprise approach views poverty and other social issues as human rights issues. This then leads it to emphasise the need to address the various causes of exclusion, discrimination and inequality in relation to issues such as peace, security, violent extremism and lack of economic opportunities.

Maria Angel Flores is the Head of Society, Philippines, and East Asia Regional Business Manager at British Council. Angela has led and managed British Council’s portfolio of programmes on civil society, social enterprise, justice and peacebuilding in the Philippines since 2014.